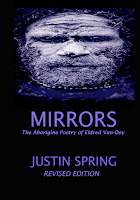

MIRRORS

MIRRORS is available in two versions

MIRRORS is available in two versions

MIRRORS is the original 2011 memoir of my translation of the pidgin poetry of aborigine Eldred Van-Ooy.

These

haunting translations have a peculiar magic all their own. You

can feel that magic if you read the pidgin silently with one eye and

the English out loud with the other. Pretend you're wearing 3-D glasses

and that I've brought you into a particularly enticing garden and left you

there for a few moments, alone, wondering, looking up at the leaves.

2016 REVISED EDITION: MIRRORS: THE ABORIGINE POETRY OF ELDRED VAN-OOY

This

is the 2016 expanded, revised version of my 2011 translation of the pidgin

poetry of aborigine Eldred Van-Ooy. In this revised version, I explore

how Van-Ooy's work was instrumental not only in changing my view of

the nature of poetry but also in unconsciously guiding me in the

creation of a contemporary version of pre-literate oral poetry

I call SOULSPEAK and a related video version of SOULSPEAK I

call Dreamstories. These are two new, revolutionary forms of poetry

that I believe some part of poetry will follow in the future. Like the

pidgin poems themselves, the 2016 revised version will leave you in a

particularly enticing garden, wondering, looking up at the leaves.

Some Previews of my Comments About the Poetry of Eldred Van-Ooy

MIRRORS is a

short memoir of my very mysterious encounter with the poetry of the Australian

aborigine Eldred Van-Ooy. It also contains translations of four poems written

by him in Melanisian pidgin (Tok Pisin). The poems were published by Van-Ooy in

a socialist Brisbane

All that I had when I started were some “Worker” microfiche containing the poems and an editorial on

Van-Ooy, all of which had been forwarded to me in 1985 by an old Australian

computer acquaintance who had come across them during the conversion of some

old microfiche files belonging to “The

Worker”.

I was able, however, to glean several biographical facts

from the editorial. A pure-blood aborigine, Van-Ooy was taken from the outback

at birth in 1891 and subsequently raised by a white, middle-class couple,

Cinque and Mildred Van-Ooy, on the outskirts of Brisbane . As an instructor at the Queensland

Institute of Technology, he achieved a modicum of local fame by designing an

ingenious waste-pumping system of vacuum and ball valves that continues to

function in the Southern Queensland Water and Sewage Management District

despite the fact that it makes minimal use of the force of gravity, the

mainstay of all such systems past and present.

It's important to remember that Van-Ooy was as well

educated as the average Australian college graduate of his time. His frame of

reference was not that of a bushman, but an educated Westerner. Some have found

my translations of the intensely literal pidgin a bit too polished, but, alas,

that is how they came to me, that is to say, my inherent sense of the

"English version" of Eldred was of a man who read newspapers and

drank tea on his patio in Brisbane, rather than someone who lived in a hut and

speared pigs, while at the same time, my inherent sense of the “pidgin” Eldred

was of someone much more primal and mysterious. For those who prefer a more

“primitive” translation—and who's to say that they're wrong—I have supplied a

literal translation of each poem in a separate section. Here is a sample of a finished translation of the "English version" of Eldred.

It's important to remember that Van-Ooy was as well

educated as the average Australian college graduate of his time. His frame of

reference was not that of a bushman, but an educated Westerner. Some have found

my translations of the intensely literal pidgin a bit too polished, but, alas,

that is how they came to me, that is to say, my inherent sense of the

"English version" of Eldred was of a man who read newspapers and

drank tea on his patio in Brisbane, rather than someone who lived in a hut and

speared pigs, while at the same time, my inherent sense of the “pidgin” Eldred

was of someone much more primal and mysterious. For those who prefer a more

“primitive” translation—and who's to say that they're wrong—I have supplied a

literal translation of each poem in a separate section. Here is a sample of a finished translation of the "English version" of Eldred.Drimtaim

DREAMTIME

Baimbai ol waitman i-singawt long mi: "Eldred."

ELDRED THEN BECAME MY NAME.

long skul, em i-singawt: "Van-Ooy."

VAN-OOY AT SCHOOL.

Behain mi go long haus, em i-singawt: "Abo."

"ABO" WHEN THE DAY LET OUT.

Yar kam na go. Olsem san. Olsem mun

THE YEARS PASSED BY. LIKE SUNS. LIKE MOONS.

Drimtaim i-kam. Drimtaim i-go.

DREAMTIME CAME. DREAMTIME WENT.

Na ol waitman i-no tokim mi em i-saevi Drimtaim.

BUT NO ONE SPOKE OF DREAMS TO ME.

Em i-tokim nem bilong olkain samting.

THEY ONLY SPOKE OF NAMING THINGS,

Em i-tokim: wan, tu, tri, wan, tu, tri, tasol.

AND NUMBERING.

Wantaim long skul mi tokim drim bilong mi.

ONE DAY AT SCHOOL I SPOKE OF DREAMS.

Tisa i-tokim mi olsem: Mi nogat saevi.

THE TEACHER ASKED

Yu tok Drimtaim long mi, orait, Drimtaim i-stap olsem ,

IF DREAMTIME ALWAYS STAYED THE SAME,

Drimtaim i-no stap, olsem de?

OR CHANGED, LIKE DAY?

Mi tok: Drimtaim i-stap olsem de:

I encountered several problems in translating the pidgin.. First of all I had to find a way of truly

understanding the pidgin. Many words and phrases can be intuitively grasped,

but some can’t. For a while, I had no choice but to guess at meanings and then

I somehow managed to locate several dictionaries, one in particular being a

dictionary on a Melanesian pidgin called Tok Pisin, which is the pidgin Eldred

had used.

But there were other problems. There was no history, no

tradition of pidgin poetry to give me some feel for what Van-Ooy was trying to

do. Pidgin, to put it bluntly, is a very strange language with which to create

a written poetry—a poetry in which the words on the page have to do everything—because

pidgin always seems comic to us. Many

times I had to make instinctual decisions as to the essential emotional tone of

a poem. This is always potentially dangerous business for a translator, i.e.,

bleeding into the original, but pidgin is so elemental I had no other choice. I

bled all over it.

Despite these inherent problems, I am sure that Van-Ooy’s

decision to write the poems in pidgin was deliberate. Expressing sophisticated

emotions in pidgin can create an incredible tension, because it stretches the

language to a point where you think it will break, or fail, and then somehow,

something in the language finds a way to say what has to be said.

Van-Ooy’s use of pidgin lets us really

feel that dangerous, beautiful tension that is at the heart of every act of

true artistic creation.

I have come to the conclusion that Van-Ooy felt, and

wanted his readers to feel the beauty of this "birthing" process: the

beautiful danger of trying to express very complex emotions in a very simple

language. You might say he wanted to remind us of the essential creative fire

within us and was willing to offer us a piece of himself to do so.

No comments:

Post a Comment